Rivers as 'quiet dialogues' and other environmental perspectives of Ala Plastica

I took the bus to La Plata on Wednesday, a city an hour south of Buenos Aires, for the second time. There I met Alejandro Meitin, a member of Ala Plastica, a group of artists who I have been ‘imagining’ now for over a year. As usual, it was my friend Hana who introduced me to them. How romantic their work sounds from afar - environmental artists working with local residents to ameliorate the polluted water systems caused by heavy industry….breaking with traditions of object-production and working instead on the scale of ecological systems ….opening up new possibilities for art in a social context.

Alejandro met me at the bus station. He is ordinary-looking, very friendly, almost uncle-like. I spent the morning with him at the Musee de la Plata (where I saw the dinosaurs I missed last week!) and the afternoon driving around, after lunch with his wife Silvina at their cosy house. As Alejandro took me to see the places where they worked I began to realise that I would not be seeing anything in particular, in the sense of a clearly demarcated project. Their work is about the production of connections, dialogues and platforms of shared work in relation to environmental issues (not only with other artists, but with other social and political subcultures), rather than projects in the object-sense that I am conditioned to understand them. Grant Kester, an art critic who writes about their work said this about them and their work in La Plata:

“Ala Plastica developed a set of interconnected projects based on a principle of social assemblage, in opposition to a number of massive engineering schemes that have damaged the ecological and social infrastructure of the region… they mobilized new modes of collective action and creativity in order to challenge the political and economic interests behind large-scale development in the region…. each of them were produced in conjunction and negotiation with activist groups, NGOs, neighborhood associations, and artists guilds in a form of what Wallace Heim has aptly termed “slow activism”… these collaborative and collective projects differ considerably from conventional, object-based art practice. The viewer’s engagement is actualized by immersion and participation in a process, rather than through visual contemplation…”

It was startling to drive around this much poorer area (in comparison with the Buenos Aires that I know), with its big petrochemical factories and open sludge-like rivers. We stopped in an old downtown once populated by workers from a meat factory that exported beef to England. It was the area in which the Peron revolution started. As we drove Alejandro talked about making small negotiations, exercises and workshops over the years to produce 'new points of view', how they weren’t only interested in articulating protest as artists but also in producing transformations.

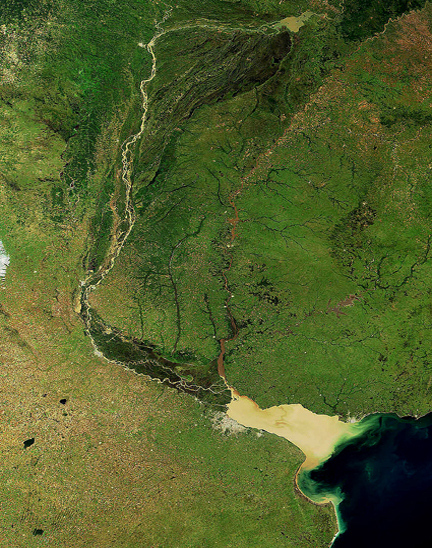

Their projects in the past few years have taken them all over the ‘bio-region’ as well as abroad. In the north of Argentina they have been involved in the recovery of a salt trail, which was once an important line of exchange for local trade and communication. Led by the founder of a salt cooperative, eleven elders from different places walked the route over eight days. The motivation was to build networks of resistance to the exploitative practices of multinational mining companies and in the intellectual property battles with pharmaceutical companies over the production of traditional medicines. In Paraguay Ala Plastica are working with a network of NGOs, philosophers and anthropologists to produce alternative plans to the intentions of government development in a region where an indigenous tribe have lived up until now without assimilation. Plans for protected areas are being drawn up based on ‘mental maps’ of places and trails of significance for the tribe´s histories and identities. These ‘organic’ plans, which differ starkly from the government imposition of a grid, explore the possibility of the co-existence of two ways of imagining the world, rather than one being swallowed by the more dominant model. I also recognised a project of theirs that Javier of Bordergames had told me about when I was in Berlin, where they worked with fisherman to create a small river bypass on which to rebuild their trade after they were displaced by the workings of a large dam.

When Alejandro talks about their work, many of his verbs begin with the prefix re-. They draw on indigenous knowledge for clues on forging new, complex connections with fragile environments - recovering values, reconnecting people, remaking histories and so on. They wrote about one of their projects: "..we generated a practically indescribable warp of intercommunication with innumerable actions that developed and increased through reciprocity: dealing with social and environmental problems; exploring both non-institutional and intercultural models while working with the community and on the social sphere; interacting, exchanging experiences and knowledge with producers of culture and crops, of art and craftwork, of ideas and objects..."

Interestingly Alejandro was first a lawyer. After university he went to work for the National Parks in Patagonia for three years before being sent overseas for four years to make contact and share experiences with other National Park services in Europe. During this time he worked with various river and pollution issues and when he returned to Argentina in 1991, he set up Ala Plastica with his wife. ‘Rivers are quiet dialogues’ he told me, in reference to their capacity to connect many different people through memories and experience.

Again I drunk up the words they use to describe their work - ‘rhizome’ to describe the multiple levels of connection they strive for, ‘place vocation’, platforms of labor and action based on the specificity of a place (in many ways I was reminded of the founding ideals of the Rural Studio), ‘bio-region’ to describe the connections between their work in different places through large-scale ecosystems, cities as ‘egosystems’. It’s funny in the scope of their limited English what sophisticated words they do know - ‘performative’, ‘dialogical’, ‘organic processes’, ‘complexity’, all from communicating about their work on international art circuits!

Their modesty made an impression on me. There was a sense of commitment and understated radicalism but there was nothing sexy about what they showed me, nothing ‘pop’, as Mauricio might say. Their documentation is very low-tech, with no branding strategy: folders with photos on coloured pages and small pieces of text cut from printed pages, films edited with basic software tools. For me, an architecture student accustomed to viewing glossy portfolios, it wasn’t even necessarily easy to really grasp what it was they did. I realised that to get a sense of the connections they are making demands experience of them over time and participation in their work.

When I was dropped off at the bus station at 5 o clock I noticed how exhausted I was from the effort of speaking in Span-glish all day about these subjects! Next week I will take them up on their offer to return and stay the night, and to discuss the possibility of doing some work together while I´m here.

Alejandro met me at the bus station. He is ordinary-looking, very friendly, almost uncle-like. I spent the morning with him at the Musee de la Plata (where I saw the dinosaurs I missed last week!) and the afternoon driving around, after lunch with his wife Silvina at their cosy house. As Alejandro took me to see the places where they worked I began to realise that I would not be seeing anything in particular, in the sense of a clearly demarcated project. Their work is about the production of connections, dialogues and platforms of shared work in relation to environmental issues (not only with other artists, but with other social and political subcultures), rather than projects in the object-sense that I am conditioned to understand them. Grant Kester, an art critic who writes about their work said this about them and their work in La Plata:

“Ala Plastica developed a set of interconnected projects based on a principle of social assemblage, in opposition to a number of massive engineering schemes that have damaged the ecological and social infrastructure of the region… they mobilized new modes of collective action and creativity in order to challenge the political and economic interests behind large-scale development in the region…. each of them were produced in conjunction and negotiation with activist groups, NGOs, neighborhood associations, and artists guilds in a form of what Wallace Heim has aptly termed “slow activism”… these collaborative and collective projects differ considerably from conventional, object-based art practice. The viewer’s engagement is actualized by immersion and participation in a process, rather than through visual contemplation…”

It was startling to drive around this much poorer area (in comparison with the Buenos Aires that I know), with its big petrochemical factories and open sludge-like rivers. We stopped in an old downtown once populated by workers from a meat factory that exported beef to England. It was the area in which the Peron revolution started. As we drove Alejandro talked about making small negotiations, exercises and workshops over the years to produce 'new points of view', how they weren’t only interested in articulating protest as artists but also in producing transformations.

Their projects in the past few years have taken them all over the ‘bio-region’ as well as abroad. In the north of Argentina they have been involved in the recovery of a salt trail, which was once an important line of exchange for local trade and communication. Led by the founder of a salt cooperative, eleven elders from different places walked the route over eight days. The motivation was to build networks of resistance to the exploitative practices of multinational mining companies and in the intellectual property battles with pharmaceutical companies over the production of traditional medicines. In Paraguay Ala Plastica are working with a network of NGOs, philosophers and anthropologists to produce alternative plans to the intentions of government development in a region where an indigenous tribe have lived up until now without assimilation. Plans for protected areas are being drawn up based on ‘mental maps’ of places and trails of significance for the tribe´s histories and identities. These ‘organic’ plans, which differ starkly from the government imposition of a grid, explore the possibility of the co-existence of two ways of imagining the world, rather than one being swallowed by the more dominant model. I also recognised a project of theirs that Javier of Bordergames had told me about when I was in Berlin, where they worked with fisherman to create a small river bypass on which to rebuild their trade after they were displaced by the workings of a large dam.

When Alejandro talks about their work, many of his verbs begin with the prefix re-. They draw on indigenous knowledge for clues on forging new, complex connections with fragile environments - recovering values, reconnecting people, remaking histories and so on. They wrote about one of their projects: "..we generated a practically indescribable warp of intercommunication with innumerable actions that developed and increased through reciprocity: dealing with social and environmental problems; exploring both non-institutional and intercultural models while working with the community and on the social sphere; interacting, exchanging experiences and knowledge with producers of culture and crops, of art and craftwork, of ideas and objects..."

Interestingly Alejandro was first a lawyer. After university he went to work for the National Parks in Patagonia for three years before being sent overseas for four years to make contact and share experiences with other National Park services in Europe. During this time he worked with various river and pollution issues and when he returned to Argentina in 1991, he set up Ala Plastica with his wife. ‘Rivers are quiet dialogues’ he told me, in reference to their capacity to connect many different people through memories and experience.

Again I drunk up the words they use to describe their work - ‘rhizome’ to describe the multiple levels of connection they strive for, ‘place vocation’, platforms of labor and action based on the specificity of a place (in many ways I was reminded of the founding ideals of the Rural Studio), ‘bio-region’ to describe the connections between their work in different places through large-scale ecosystems, cities as ‘egosystems’. It’s funny in the scope of their limited English what sophisticated words they do know - ‘performative’, ‘dialogical’, ‘organic processes’, ‘complexity’, all from communicating about their work on international art circuits!

Their modesty made an impression on me. There was a sense of commitment and understated radicalism but there was nothing sexy about what they showed me, nothing ‘pop’, as Mauricio might say. Their documentation is very low-tech, with no branding strategy: folders with photos on coloured pages and small pieces of text cut from printed pages, films edited with basic software tools. For me, an architecture student accustomed to viewing glossy portfolios, it wasn’t even necessarily easy to really grasp what it was they did. I realised that to get a sense of the connections they are making demands experience of them over time and participation in their work.

When I was dropped off at the bus station at 5 o clock I noticed how exhausted I was from the effort of speaking in Span-glish all day about these subjects! Next week I will take them up on their offer to return and stay the night, and to discuss the possibility of doing some work together while I´m here.

» Post a Comment