Driving over the state line into Alabama...

[dating back to Feb 13th] [Chapter One of Four from Alabama trip]

.....is the closest I feel to going home on this side of the Atlantic, the once alien strip malls and trailer parks of the interstate landscape now seeming completely normal. But the Alabama which fires my imagination is found on the back roads, the charming if dilapidated Main Streets of once thriving small towns, the beautiful barns falling into disrepair, the abandoned family gas stations advertising at a dollar a gallon. I still believe the genius of The Rural Studio is in how it reverses the direction of the talented student, if just for a few months, and reinvents the rural landscape as a place of opportunity. In a way the most remarkable spatial organisation it has produced is not in the quirky forms of its portfolio of houses but rather in the colonisation of downtown Greensboro by young, energetic spirits who, without the usual roster of urban activities to fill their time, start occupying places and landscapes in new and creative ways. With a critical mass of like-minded people there and a steady stream of interesting people constantly coming through, living in Hale County became a giant adventure for me, fuelled by the exhilaration of opportunity and responsibility, the freedom of open space, of time spent outside, of a low cost of living, of a slower pace of life.

In the meantime, because of or in spite of the Rural Studio (who knows?), almost all of the Main Street stores in Greensboro are doing business, a dramatic contrast to any other comparable town we drove through on the way. There are now five or six renovated loft spaces, as opposed to two in progress when I was there. Once storage for the goods and grains sold in the stores below, they are now transformed into amazing living spaces with 18ft ceilings, ornate pressed tin ceilings, wainscoting and fireplaces, huge sliding doors, and clawfoot bath tubs rescued from old barns. Emily and Daniel, whose apartment we stayed in for the week, are living in theirs rent-free after a heroic renovation effort that is basically on-going.

Before arriving in Greensboro we had driven from Texas (deciding foolishly to take the scenic route, which meant we were still in the state seven hours after we left Austin) to Starkville, where we stayed for a couple of days with Jay, who is working at the Small Town Center, part of Mississippi State School of Architecture. Starkville is an intriguing place, with all the usual features of a small college town in the South - a charming downtown complimented by a sprawl of strip malls – but also with this curious little ‘new urbanist’ district where Jay lives - where you can find every type of classical building style packed densely into six blocks, from mini greek temples inhabited by frat boys, to brick terraced houses facing onto cobbled streets reminiscent of northern British towns, to three storey townhouses, almost unheard of outside the big cities. A gourmet food store, a wine bar and a cheesy margherita joint all within walking distance of Jay’s 150 sq ft studio which the three of us plus two dogs squeezed into. It’s been built up incrementally over forty years by one guy, now the mayor of Starkville, and though it might feel a little like a film set and be dominated by college students, all things considered I’d live there before a brick ranch house suburb any day.

The Small Town Centre has an admirable but difficult mission: advising small towns suffering the effects of policies outside their control – loss of their agricultural base predominantly - on new economic visions for their town. While I was there they were getting ready for a mayors of Mississippi conference. Meanwhile it seems like their post-Katrina work on the Gulf Coast is being somewhat overshadowed by the slick presentations of Andres Duany and his band of New Urbanist evangelicals.

The video camera got its first important outing save for its bumping around out of the car window across Texas, which resulted in at least an hour of completely useless footage. A two hour interview with Jay about his time at the Rural Studio (four years!) and his take on the participatory process (my research subject) was the perfect wake up call after three weeks with my nose in books and my consequent idea of what it meant. Writers on the subject will tell you that the participatory process is one that is not framed exclusively on the terms of, and by the tools of, the designer. Rather, to avoid a singular interpretation (that of the designers) of a situation that may be driven by different sets of values to the users, supple methods are required that interpret needs and desires which may not have been articulated before, particularly not in conventional architectural language. Though they might be translated eventually into an architectural proposal by the designer, the input may not begin life in these terms.

What I realised I hadn’t understood, until listening to Jay talk about his projects, is that a participatory design process which does not begin with discussions over plans and sections, details or materials, may never arrive at those aesthetic or technical discussions either. The designer may still make those decisions alone, but shift the process and language which informs those decisions. For example…Jay and his teammates were building a new backstop for the Newbern baseball team. They were attending the games but their attempts to engage the crowds and players in design conversations were unsuccessful. They organised a town meeting in their studio, where they dutifully pinned up drawings, eager to receive feedback about their ideas. But only three people showed up and they had little to say about what they were shown.

Did this mean that the team didn’t care about getting a new backstop? Not necessarily, but the way of talking about it was completely and utterly alien to the players, who had never encountered an architectural drawing before or thought about their backstop in terms of materials and details. In the end one Sunday Jay was invited to pick up a bat. From then on he played every week with the team for the rest of the season, while his teammates continued to make friends in the crowds. Over this time they came to notice certain things about the way the existing layout was ordered – all the bleachers were shaded in the afternoon with the bench of the away team being the only one that wasn’t, all the vendors had their same spot for selling catfish or beer each week. These observations led them to drop all their plans for new architecturally interesting seating plans and quirky vendor booths. When the end of the season came they took down the old fence with the help of some of the team and simply built a new and beautiful sculptural backstop of steel columns and chainlink fencing - decisions about which had been made entirely by them, but based on their months of attending and playing at the games.

When the baseball season started back up Jay said, to my surprise, that no-one particularly commented on it. Baseball continued as it always had done, the same food being cooked, the same teenagers strutting, kids playing and young guys competing for the flashiest rims on their tyres. When we tell stories of the Rural Studio people like to hear best the tales of transformed lives, perhaps the baseball team who went from losing every game to the top of their league courtesy of their new field. But in fact, perhaps fortunately, it is much more subtle than that. Was it a participatory design process? Maybe not in the way that I read in my books it should be. But in the fact that Jay played on the team for four years, becoming in the process a trusted and integral part of that community and able to make decisions in that context, I think more so than any kind of survey process could ever be. The backstop continues to impress visiting architects and new students with its detailing and gracious form and for everyone else, it probably does a better job than the last one of keeping stray balls in the field.

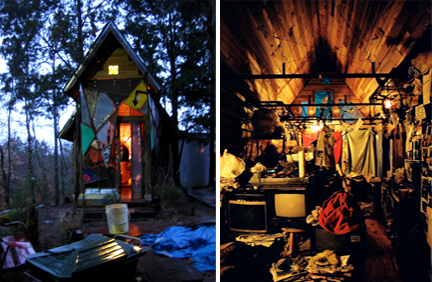

Likewise, in building a house for Music Man - a prophetic, eccentric, charismatic bachelor who communicates in a completely different way to anyone I’ve ever met - a conversation about walls and doors and materials is simply never going to unfold in a way that helps you make straightforward design decisions. Instead, as second year instructor, Jay encouraged students to spend time on site, clearing the vegetation, going to church with Music Man, building first a small room he was able to move into from his dilapidated trailer. That same room also allowed them to build mock-ups of the details for the house and to speculate about how Music Man might inhabit his future home. There were endless debates in the studio that I can remember about what kind of attitude should be adopted in relation to Music Man’s passion for hoarding, particularly plastic bottles and bags and redundant electronic equipment. The space in which he lived in his original trailer was actually carved out of a dense mass of these agglomerated objects. Should students try to reform his unhygienic penchant for ‘junk’? In the end a decision was made to build a house with a really tall pitched roof, which would retain a feeling of spaciousness even if he filled the house up again after a few years. Sure enough, three years later exactly this has happened and the generous roof pitch performs just as the designers hoped it would. No-one really knows if Music Man ever uses his shower and toilet which he never had before this house. And as close to him as we are in a funny way, I don’t feel like I’ll ever really understand what moves him to label and retain every bag and bottle he comes into contact with, to record every movement and visitor on a piece of paper and attach it to a clothes line that is strung across the middle of the room, to store his giant speaker and guitar in his bathroom. But that really is part of the magic of knowing him, the poetry of coming into contact with a reality so far from your own and finding friendship nonetheless.

» Post a Comment