B ring New Orleans Back – the mayors co-ordination effort…….see the initial reports

here.

C onferences. Everyone is holding them. I spent a lot of my time with the organisers (Dan Etheridge and Alan Lewis) of this one -

Reinhabiting NOLA - a collaboration between the Xavier Center for Bioenvironmental Research, the Tulane School of Architecture and the Neighbourhood Story Project. The conference last November brought together 150 academics, professionals, scientists, artists, community leaders and environmentalists for two days in New Orleans and included a number of displaced residents who were flown in for the weekend.

D evelopment. While I was there the 'rebuilding' media focus was on a plan labelled ‘neighbourhood viability’. To receive reconstruction funds a neighbourhood must prove its ‘viability’ through a critical percentage of returning residents and its adjacency to two other qualifying neighbourhoods. Many potential rebuilding efforts were on hold until the release of

FEMA base flood elevation maps this month.

E arth Science Perspective on Katrina. A lecture I went to on my first evening and my introduction really to the environmental complexities of the situation. Louisiana has 40% of the US coastal wetlands, which protect against storm surges and are estimated at an economic value of $5 million per square kilometre. Monitoring of the coastal wetland loss in the 1980s measured an acre being lost every 30 minutes and identified it as the most severe environmental problem in the country. Caused in large part by the interference of natural systems by the levees, the wetland loss problem was exacerbated by the oil and gas industries in the last century as they dredged commercial shipping canals that in turn created open passages for storm surges. I felt very indignant about the fact there were only nine people at the lecture until I realised that dozens of

talks and discussions are taking place every day across the city....

F EMA. Of course is the easy scapegoat. I don’t really know enough to comment on the numerous and fierce accusations of incompetency, cronyism and no-bid contracts but one anecdote from Ronald Lewis, a resident of the Ninth Ward, really struck me. He was part of a self-organised rebuilding effort when Hurricane Betsy devastated the Ninth Ward in 1965 and there was no FEMA to step in. Ronald was assigned to a community sheetrock team that redid twenty to thirty houses in the neighbourhood. His opinion: FEMA has disabled people’s ability and will to self-organise while failing to provide any more effective alternative.

G round. “This city is built on chocolate mousse”

I -10. When the massive I-10 was built in the sixties it bisected many lower-income neighbourhoods with no consultation process at all. In the Sixth Ward the giant concrete columns of the freeway have been painted with live oaks and mythical imagery, a neighbourhood’s way of reclaiming their lost space. The offer to help ‘Rebuild’ is thus treated suspiciously in many communities – I-10 was just such a project.

J ournalists. Contrary to popular reporting New Orleans is not a city below sea level. More than half of it is at or above sea level, making it similar to hundreds of coastal cities across the world. Nor was the flooding restricted to low income neighbourhoods, it in fact cut across racial and class boundaries, devastating, as well as the Ninth Ward, the middle to high income neighbourhoods of Lakeview that were built on land reclaimed from swamps and the lake around the fifties.

L evees. The levees actually collapsed in three places, each efficiently wiping out a different area of the city. It turns out that at no point were they ever holding any more water than they had been designed to. So their failure was one of construction more than anything else. All around the Ninth Ward there were signs asking for witnesses of the levee break. Rumours abound that they were dynamited. Dan told me that there was actually a precedent for this. In the early 1900s men would guard the levees on their side of the river during storms in case a neighbour on the opposite side tried any tricks. Even if there was no actual dynamiting in 2005, in Dan’s opinion there was a metaphorical ‘dynamiting’ over the years as commercial shipping interests were systematically privileged (and heavily subsidised) over the interests of residents of the Ninth Ward and beyond.

M ississippi River Gulf Outlet (Mr Go). It was the widening of this canal from 500 ft to 2500 ft in the sixties that encouraged the storm surge that devastated the Ninth Ward. Calls now are for the canal, which was an economic drain anyway (only two to five ships use it each week) to be closed immediately. Ideas have included using all the waste from the storm to dam it, which though not environmentally sound may be better than it all going to landfill. Right now all the wood waste is being turned into wood chip mulch by Halliburton to be sold nationwide. Not sure if it will specify its potentially toxic origins.

N eighbourhood Story Project. An inspiring documentary project that is collaborating with the Tulane School of Architecture. It empowers high school students to record the stories of people, traditions and histories in their neighbourhoods and in doing so to challenge the negative stereotypes of those areas often perpetuated by the media. The by-line of the program is ‘our stories told by us’. I was at a seminar led by Rachael, an anthropologist and one of the founders, and Ashley, a student who wrote one of the six books that were published just before Katrina. Ashley is a resident of the Lafitte housing project which has been closed by the authorities since the storm. The most striking things she said during the seminar: “I didn’t know I lived in the ghetto…..…..till I heard it on the TV”. Hear her on New Orleans Indymedia Radio

here.

O pposition. A group from an area called Broadmoor published an article in the

Gambit about their self-organisation into an activist group after coming across a diagram in which their neighbourhood had been replaced by a large green circle. The story recorded their anxiety to find out what that meant and their anger at the lack of consultation with them. Various phonecalls unveiled the fact that it was part of a hastily drawn up plan by a Philadelphia group in a very short amount of time and that it was not in any way a fixed plan. The green circle apparently indicated ‘where a park could be’ if residents agreed. An interesting illustration of the politics of representation and the problem of interpretation. It also seems to have been a catalyst for an impressive amount of

neighbourhood organisation.

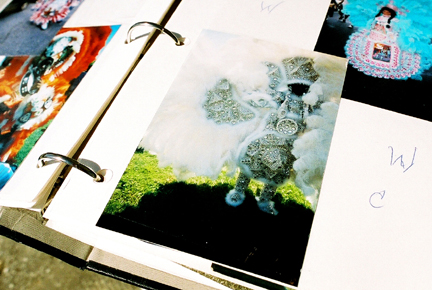

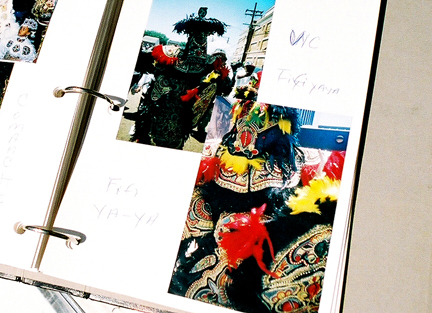

P arades. The wonderful tradition on which New Orleans has built its cultural energy. During ‘second line’ parades the audience and performers form one dancing, singing crowd that winds through the streets for hours, stopping to honour places of community significance, churches, stores, people’s homes, and honouring the recently deceased. Rival ‘Social and Pleasure Clubs’ exist purely to organise annual parades, which are funded, with a considerable amount of sacrifice, by members of their community. Rachael described it as the cultivating of ‘cultural resiliency’. I imagined this in the context of bureaucratic interpretations of ‘urban renewal’ processes. There was a big debate this year about whether Mardi Gras should be cancelled and the money put aside for rebuilding, but this missed the point that parades have been an embedded part of the social and cultural renewal of the city fabric throughout its history.

R onald Lewis. A long time resident of the Ninth Ward - architecture students from Kansas State are working to rebuild his Museum of Dance and Feathers, which was once housed in his carport. Ronald is a Mardi Gras Indian costume maker, an artist who spends all year making intricate beadwork costumes for parades. His museum contained all his costumes, as well as newspaper clipping and photos dating back decades, objects which are impossible to value for an insurance company. He saved perhaps 10% of his collection - beautiful beadwork patches and photo albums full of people in costume with wonderful Indian names. For Rural Studio folks, Ronald blends Amos’s patriarchal nature, AJ’s artistry and Music Man’s all-consuming spirit. He is hoping that as he rebuilds, others in the neighbourhood will gain the confidence to as well. He hosted a crabboil one night which functioned both as a crit with the students and a party for neighbours who have returned. What better review than to have drawings pinned up on the side of a house on site, with a torch illuminating them in the fading light, beers in hand and Cajun sausage on the grill? Here him on NPR

here.

S ixth Ward. The area in which Tulane has chosen to locate its pilot Urban Build studio (see ‘U’). It is one of the traditionally working class neighbourhoods that form a belt through the centre of the city. The Sixth Ward is within seven blocks of the French Quarter, an example of the surprising spatial integration across New Orleans. It is basically at sea level, and because of its proximity to wealthier areas it is likely to be awarded ‘neighbourhood viability’. It is a neighbourhood of extremes; dilapidated and cramped, full of ragged structures, vacant lots and isolated families occupying only one or two porches on every block, but imbued nonetheless with the vibrancy, vitality and intense charm of historic New Orleans that knocks you sideways.

T ulane. The university is in a particularly interesting position to co-ordinate a powerful network of action both locally and nationwide, at a grassroots level and at a political level. Reed Kroloff and Ila Berman, the Dean and Associate Dean respectively, are on the Mayor’s Urban Design Committee. Meanwhile every one of the ten design studios at Tulane has been charged with tackling an aspect of post-Katrina New Orleans this semester. In addition they have started a nationwide design/build consortium, the

Tulane City Center, to co-ordinate the energy and resources of all the schools who are interested in working in New Orleans. In conjunction with Architectural Record, they held a prototype

housing competition, the entries for which I helped unpack and display for the jury session (which I didn’t get to be present for!). And see

here proposals they also commissioned from a series of Dutch and American firms for a ‘radical’ rethink of the city at various scales. This is all going to result in a series of different exhibitions across the city at the end of this semester.

Oh, and Reed Kroloff is also engaged in an all out war with the New Urbanists, ‘the ‘Mcdonalds’ of architecture, according to Ila Berman, who are literally knocking on the door of New Orleans after sweeping along the Mississippi Coast with highly organised charettes and attractive hand-drawn watercolours. His article in Metropolis in March claiming 'to be black' caused quite a stir. Read it

here and some of the responses to it

here and

here.

T rees. One way to tell which areas flooded is to look at the trees. Magnolias don’t fare well in salt water and are dying all over the city. In contrast live oaks are fairly resilient. They are some of the most magnificent structures in the city, their roots heaving up huge chunks of the pavement everywhere you walk. It is striking to drive along the Gulf Coast where barely a single house, casino or commercial strip remains but where all the ancient live oaks still stand, the secret lessons of survival embedded in their roots far under the soil.

U rban Build. This is the studio that emerged from the ‘Reinhabiting NOLA’ conference. A double pilot studio is up and running, hoping to expand to six studios running concurrently if all goes according to plan. One studio is working on an affordable prototype for a house in conjunction with a community centre and affordable housing group in the Sixth Ward. The other is trying to tie that project into a larger scale vision for the neighbourhood as a whole, in my opinion a much harder project to take on as a ‘real’ project. At the scale of the single house the relationships are manageable and the boundaries clear, and the studio a well-adapted setting for carrying out intense collaborative student work. These relationships and boundaries become infinitely more complex at the neighbourhood scale, particularly in this situation. As a result students at the mid review seemed to have stayed within the safe boundaries of what can be physically measured - massing, street layouts, ‘green space’ (the apparent cure for all ills) - and represented through diagrams, while marginalising the social complexities of the area and failing to acknowledge the value systems which allowed them to casually demolish an entire housing project with the click of a mouse. Despite a claim to community consultation I searched in vain for one anecdote of an interaction with a resident which informed someone’s strategy.

V olunteers. The only people virtually to be seen in the ghost towns of the Ninth Ward and similar areas were clusters of students gutting houses on what had been termed the ‘alternative spring break’ project.

W aste. Toxic mostly. After the storm there was six feet of polluted sediment in some areas. The sediment has been cleared but the environmental hazards remain uncertain. The EPA is delaying making any sort of definitive statement about it, claiming more studies are needed. Barrels of DDT from a factory that once made Agent Orange during the Vietnam War were found in people’s living rooms. A consortium of architects and community groups have started the

Katrina Furniture Project, a recycling and craft program which will train young unskilled workers in furniture making using the waste wood from the storm. And you can normally tell how many people are back in a neighbourhood by how many piles of debris there are outside people’s homes.

X. An aggressive, fluorescent branding marks each house in New Orleans, indicating when and by whom they were inspected after the flood. The number at the top marks the date, to the side which authority checked it, and at the bottom how many dead bodies were found. I’m glad to say that I only ever saw zeros.

Z ero feet above sea level. An extraordinary datum now exists across the whole city, the brown watermark scar on buildings which allows you to read how far the ground is below sea level at any given point. As you drive from Lakeview near Lake Pontchatrain back into the city it gradually decreases from eight feet and over, down to two or three until finally it disappears when you reach Uptown and the Garden District.